June 28, 2025

I’m going to be honest: I don’t fully understand the practical impact of the Supreme Court ruling on birthright citizenship yesterday. It is not a ruling on the merits, though it slightly shakes my confidence that the court will uphold 127 years of precedent around the 14th Amendment. “Settled law,” as much as all the recent appointees talked about it in confirmation hearings, seems to be not their thing.

At issue was the ability of a district court to issue a nationwide injunction on action being challenged in court that would cause irreparable harm to parties to the case. The court ruling, written by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, limits this ability. But what is the practical significance?

There may not be any practical significance:

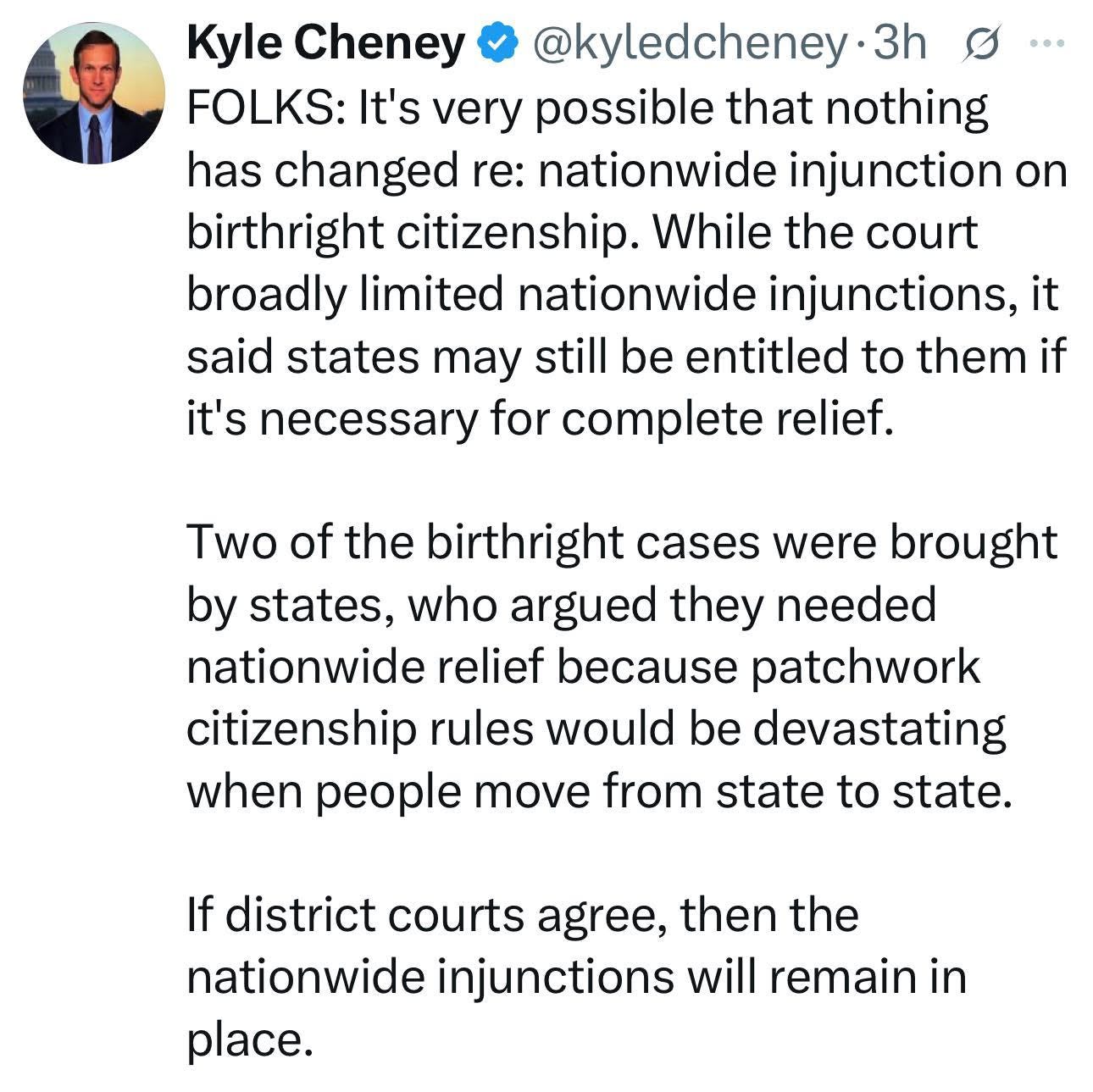

This morning, there is a little more clarity about what the court did, showing the limits of the limits they imposed:

But suppose we just take the idea that district courts generally cannot impose universal or nationwide injunctions as given. That would mean, I think, that the district court judge can only grant that relief to the plaintiffs.

In this case, the plaintiffs are the 22 states that brought suit. In those states, there will be a stay on the executive order; every child born in one of those places will be a citizen, while those born in the other 28 states, at least until the case is decided, will not.

Assuming this were to remain the case, a person born in Massachusetts would be a citizen, and presumably Mississippi would be required to recognize it. Suppose an immigrant woman living in Chicago takes a trip to Austin, where she unexpectedly gives birth early. She and the baby go back home, with his Texan birth certificate. Is Illinois required to not recognize the boy’s citizenship? Suppose the mother already had two children, both born at home; in this case, one of her three children would be unable to vote, work, and might be subject to deportation if they crossed back into the Other 28 – or from their Chicago home, if the federal government decided to take action.

What would have happened if the case had been brought by individual plaintiffs rather than the states? Say, pregnant H1-B visa holders. Would a judges injunction apply only to them? Would it apply only, say, in the Southern District of New York? In that case, could a person born in Brooklyn hold a job in Manhattan?

In short, disallowing universal injunctions invites chaos. More than this, it invites bifurcation among the states depending on decisions in different circuit courts, something that might make travel and perhaps trade difficult across certain state lines.

There will eventually be a ruling on birthright citizenship, and there will eventually be a ruling in all the cases where the lack of universal injunctions creates fractures in the law, but what would be the impact of constantly having these kinds of disjunctures, where the law is very different in the fifth circuit from the ninth, where more liberal states operate under different interpretations of federal law than conservative ones, for two years at a time, again and again and again? Will that not weaken our commitment to the idea of e pluribus unum?